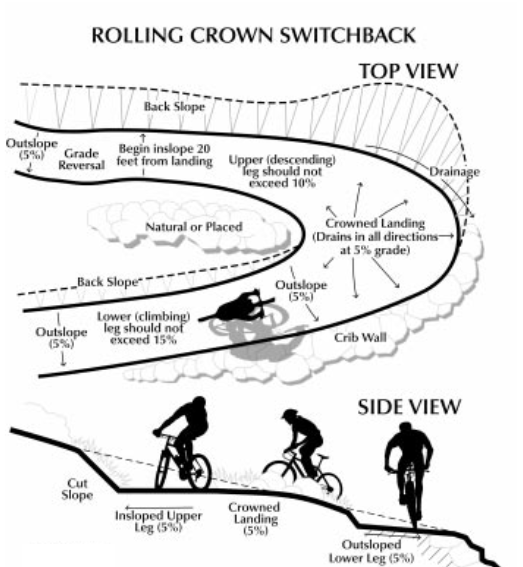

“What makes switchberms different than rolling crown switchbacks [depicted above]?

-the leg just above the turn is a gentle grade, keeping speeds in check for descending riders (5%-8%).

-the turn is on a nearly level platform and slightly bermed (insloped 6%-9%).

-the climbing leg below the turn is brief but quite steep (15%-20%, or just a bit more if you need to push it).

-turning diameter is between 14 feet and 18 feet depending on width of trail, sideslope and intended users.

Do all you can do not to exceed grades above 20% for the lower leg steepness — this is where overall trail analysis is needed before you start digging.

Obviously, for bike parks and fully bike-optimized turns these would be used only as a last resort. Bike park turns, and turns designed for one-way bike traffic with higher speeds, generally should be built on fairly gentle sideslopes, allowing for a much bigger turning radius with a diameter of 22 feet or more.” source: imba mark-eller

Hans with Bellfree Contractors has been doing this for some time now, with an added entry berm made for countersteering into the switchberm:

^Three Hawks at Crafton Hills…also evident at Santiago Oaks on Bumble Bee, and some other Bellfree trails.

Palos Verdes below:

^hard to see the reversals before and after the turn

^hard to see the reversals before and after the turn

slightly different ways to berm and drain below…also a little hard to depict the grades on film:

Climbing Turns

source: Next to waterbars, climbing turns are the trail structure most often constructed inappropriately. The usual problem is that a climbing turn is built (or attempted) on steep terrain where a switchback is needed. A climbing turn is built on the slope surface, and where it turns, it climbs at the same rate as the slope itself. If the slope is 40 percent, the turn forces travelers to climb at 40 percent. It is almost impossible to keep a climbing turn from eroding and becoming increasingly difficult to travel if the slope is steeper than 20 percent [if not 10% or less].

The advantages of climbing turns in appropriate terrain is that a larger radius turn (4 to 6 m, 13 to 20 ft) is relatively easy to construct. Trails that serve off-highway-vehicle traffic often use insloped, or banked, climbing turns so that riders can keep up enough speed for control. Climbing turns are also easier than switchbacks for packstock to negotiate. Climbing turns are usually less expensive than switchbacks because much less excavation is required, and fill is not used.

The tread at each end of the turn will be full bench construction, matching that of the approaches. As the turn reaches the fall line, the amount of material excavated will decrease. In the turn, the tread will not require excavation other than that needed to reach mineral soil.

Guide structures should be placed along the inside edge of the turn. Temptation-reducing barricades can be added if necessary. The psychologically perfect place to build climbing turns is through dense brush or dog-hair thickets of trees. Be sure to design grade dips into the approaches.