This is a long post, maybe a diatribe, that could grow into a book in itself. It has had several editions since it first appeared. There are some books referred to throughout the post that are applicable to trail user group issues if you wish to explore conflict resolution and group dynamics further. In the end what’s presented is a solid case for shared use trails. There is also a case for single use trails, but as you will see the case is not as strong. also see: DOT-FHWA Study- Conflicts on Multiple-Use Trails ( more studies ), Perception and Reality of Conflict: Walkers and Mountain Bikes.

PDF of this page: Shared Use Trails

Related: Beyond Shared-Use Trails

Introduction and Groundwork:

Although there are some trail ‘science’ arguments for shared and single use trails, most of the topics surrounding this issue are better placed alongside law, logic, reasoning, psychology, and philosophy, not science.

Non-erosive sustainable trails can be laid out for all user groups using planning with ‘science’ and engineering. The same can be implemented to limit conflicts as well. The debate on shared vs. single use trails ultimately comes down to philosophical arguments, as the conflicts can be managed through design and construction, not to mention a little education.

There are some minds that will never change in regards to the debate of which uses should be allowed on what trail. Some people may have no argument other than to be with their own kind. They have little to zero patience when it comes to sharing a trail, and perhaps the road for all we know. Sometimes it even involves “bikelash.”

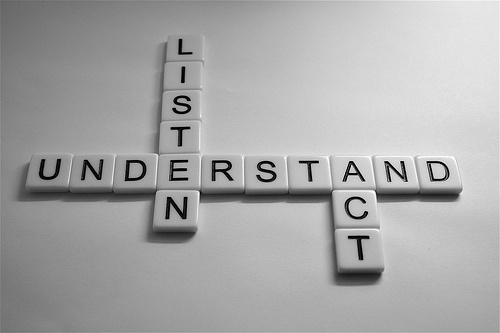

Sharing a trail can involve interaction, but quite often users only pass each other with only a nod or wave. Exchanges could involve a simple hello or an exchange of words from shallow to deep if inspired. Judgments may or may not be exchanged by the interaction or glances. Some people will “tolerate” other people’s differences, others not. I wholeheartedly believed in tolerance at one point in my life. I suppose there are some things I still tolerate. However, I now prefer to “understand” because of something Wendell Willkie said: “tolerance is the assumption of superiority” (also see this). I realize I can’t always “understand” other people’s culture, religion, or the tribulations that made them who they are, but I feel better “understanding” (the best I can) rather than tolerating. This attitude towards tolerance flies in the face of the denotation most people have for tolerance, but considering Willkie’s statement (and what will be said below), the connotation is that tolerance harbors a little hate (and sometimes a lot).

Although we can never truly “understand” other people, on a basic level we can understand that freedom of thought and action, or liberty/sovereignty if you will, is what makes all of us who we are. I don’t feel comfortable tolerating (and even  understanding sometimes) a person doing certain things as it doesn’t seem like it’s my place, because they are not me. Understanding, to put it crudely, is believing “to each their own,” and to some degree “minding your own business.” Not that you can “understand” someone by minding your own business, but more in the sense that some businesses don’t do business together, but they get along just fine doing what they do. I don’t know what to equate tolerance to in this effect, perhaps wishing you could ‘get in someone’s business’ and own what they do, not necessarily ‘treading on’ them, but contemplating it or finding a way to stifle what it is you don’t like about what they do. On some level understanding is closer than tolerance to love, compassion, or empathy, or similarly an outright carefree attitude towards what someone else does.

understanding sometimes) a person doing certain things as it doesn’t seem like it’s my place, because they are not me. Understanding, to put it crudely, is believing “to each their own,” and to some degree “minding your own business.” Not that you can “understand” someone by minding your own business, but more in the sense that some businesses don’t do business together, but they get along just fine doing what they do. I don’t know what to equate tolerance to in this effect, perhaps wishing you could ‘get in someone’s business’ and own what they do, not necessarily ‘treading on’ them, but contemplating it or finding a way to stifle what it is you don’t like about what they do. On some level understanding is closer than tolerance to love, compassion, or empathy, or similarly an outright carefree attitude towards what someone else does.

Why carry on about tolerance vs. understanding in regards to trails? To add one more cliche, or platitude according to some, to the ones used above: “put yourself in another user’s shoes.” On some level understanding trail users is the trail head all users need to remember when they feel themselves slipping from understanding towards tolerance, or worse outright hate. In other words, begin by understanding yourself and why you use trails, and afford others the same right and dignity. As we go on I hope this will all make a little more sense.

Is-Oughts and Ethics

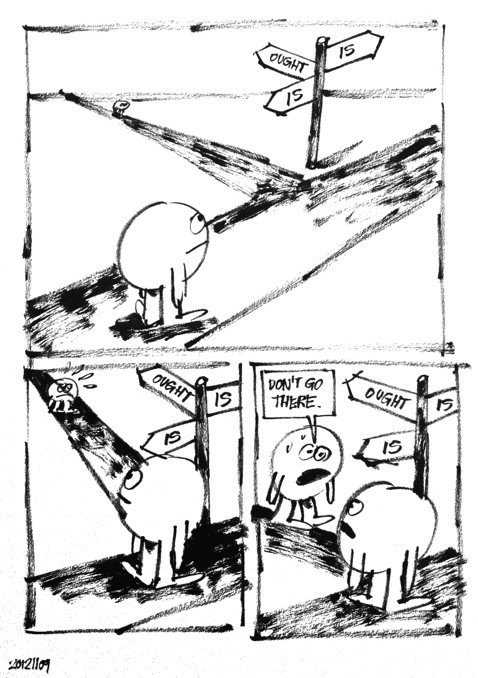

First, lets make the entire trail use debate very messy and take into account (as we have to) meta-ethics and moral science. Where do the trail use decision makers  stand, are they moral realists or relativists and from what vantage point? I make some normative moral relativist arguments in this diatribe, but in then end I’m trying to escape Hume’s Guillotine with an ethical realist/naturalist and utilitarian approach.

stand, are they moral realists or relativists and from what vantage point? I make some normative moral relativist arguments in this diatribe, but in then end I’m trying to escape Hume’s Guillotine with an ethical realist/naturalist and utilitarian approach.

Hume’s Guillotine splits an is and an ought to separate the two as a means to say an ought can’t be derived from an is. Trail use arguments are oughts derived from an is: “this is a trail, it ought to be hiking only.” Most people see this statement as a bundle this way: “this trail is hiking only.” The title “hiking only” seems axiomatic or self-evident, but what rights, moral duties, or oughts derive from this rule? The “only” inference in “hiking only” only matters in a dispute between two people, over who ought to own what— exclusion. The “trail” is a descriptive statement (what is), and the right to exclude others (hiking only) is a prescriptive/normative statement (what ought to be).

To say “this is a trail, it is hiking only” is partly right as the is needs to be combined with an ethical statement to get an ethical ought conclusion. To Hume oughts can’t be derived “exclusively” from an is, because the is must be tied to an ethical statement. For example, the utilitarian approach would be: “obeying X increases happiness, therefore X is the right thing to do.” However, this is a tautology (where the ‘right thing to do’ is to increase ‘happiness’– unnecessarily redundant) and still an ought. The ‘right thing to do’ is an ought, and ‘happiness’ is an is. A “hiking only trail” is a bundle that confuses the ‘right thing to do’ (rights of individual sovereignty and property (ethics)) with the is of ‘happiness’ (existence or metaphysics/epistemology). Ethics attempts to make an is from ought.

- factual/is premise: poaching for x reason on a hiking only trail causes unhappiness

- ethical/ought premise: it is wrong to cause unhappiness

- ethical conclusion: poaching for reason x is wrong

It could also be said:

- factual/is premise: poaching for x reason on a hiking only trail causes happiness for the poacher

- ethical/ought premise: it is wrong to cause unhappiness

- ethical conclusion: poaching for reason x is right because the poacher is happy

another framing:

- factual/is premise: excluding users from a trail for reason x causes unhappiness

- ethical/ought premise: it is wrong to cause unhappiness

- ethical conclusion: excluding users for reason x is wrong

The shared use debate can be so combative because it centers around oughts, whether the debaters think about the is-ought problem or not. All trail use designations, shared or single, are oughts. It could be argued that the single or restricted use position is weaker because it makes normative claims of exclusion, and the more user types allowed on a trail the stronger the case for a trail’s existence (or is) because the the trail becomes closer to being just an “is,” not an “ought.” Access rights are civil liberties that can sometimes be tied to ‘natural’ rights of property, but the connection of so-called natural rights to the use designation of trails is pretty weak. Furthermore, even the idea of “rights” could be argued to be metaphysical or subjective to make the trail use debate even messier. Ethics is messy enough without considering this latter problem.

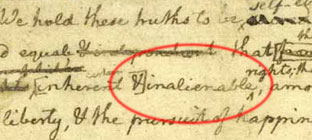

Rights and Respect

It was John Locke who inspired America’s founders with talk of unalienable rights, arguing that we have a right to our lives, resources for life, and what we produce. A trail could be seen as a resource for life, but just how essential is debatable. Ruler and ruled according to Locke are against nature.  If we are all sovereign, there is no master sovereign, so no one may rule– slavery, serfdom, or involuntary servitude are forbidden. Rights are an ought border, liberty is a borderless is.

If we are all sovereign, there is no master sovereign, so no one may rule– slavery, serfdom, or involuntary servitude are forbidden. Rights are an ought border, liberty is a borderless is.

Natural law proponents have to answer why laws, if natural and universal, are often a dilemma of self-interest vs. the interest of others, including that of the rule makers? Should any principles of conduct be followed or are the makers of those rules just promoting their own interests? I can’t answer these questions, but at its core it comes back questions of ethics/morals and to sovereignty, and the means by which we can avoid conflicts to afford equal sovereignty to all– reciprocity in liberty and justice, not to mention a respect of ethics. Give respect to get respect. Easier said than done, but something to remember when using and advocating for trail use designations.

Is and ought aside, if I’m hiking and see a horse back rider or trail runner I understand the trail runner better than the equestrian because I often run on trails, but I still understand the horse back rider. I might not know exactly what makes or inspires either user to get out on the trail, but they are there, like me, and that’s all that matters. I can only hope they are getting what it is they need, because that’s why I’m there too.

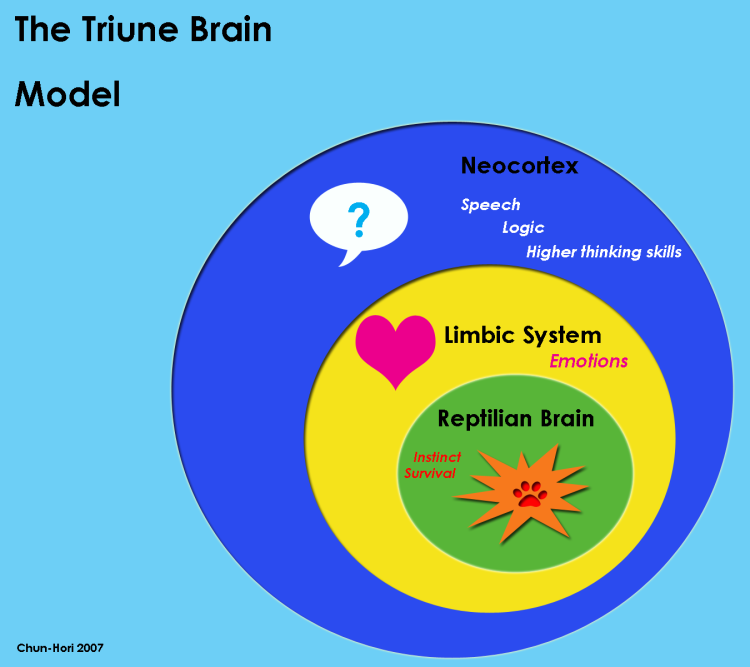

Brain versus Gut

Quite often what we are dealing with when it comes to shared versus single use trails are ‘gut feelings’ and outright bigotry, not rational thought. People jump from is to oughts and use their primitive brain stem, not their brain. Joshua Greene showed this using the thirty-year old Trolley Problem. Greene ultimately asks what morals are good/bad (meta-morality), not what is good/bad (morality). The former allows different groups to get along, the latter individuals in those groups. They are connected. The group is a group usually because of a shared set of values held by individuals. The difficulty is in getting two groups with different values to be a group as well– meta-morality.

Quite often what we are dealing with when it comes to shared versus single use trails are ‘gut feelings’ and outright bigotry, not rational thought. People jump from is to oughts and use their primitive brain stem, not their brain. Joshua Greene showed this using the thirty-year old Trolley Problem. Greene ultimately asks what morals are good/bad (meta-morality), not what is good/bad (morality). The former allows different groups to get along, the latter individuals in those groups. They are connected. The group is a group usually because of a shared set of values held by individuals. The difficulty is in getting two groups with different values to be a group as well– meta-morality.

Utility and Genetic Disruptions

The ultimate goal in trail use designations should be to provide the most happiness (utilitarianism) and Pareto optimal situations (described later), but this is hard when quite often the trail user rights issue is emotional,  not logical. And if people wish to quantify happiness it can get ugly (see the poaching examples above). This is complicated by opposing groups feeling superior, and more wronged than the other group in reaching a resolution on how to cut the trail cake. On that note, the correct focus is meta: are trail user division rules good or bad for trail x, and why? The incorrect focus is: which trail use type is ‘moral’? Related to the focus problem is the problem of our very selves, our genes, and how they tell us to think. Evolution equipped us with group cohesion, not meta-morality. That’s why some people slip into focusing on the ‘morality’ of a user group, not how to get along and use a trail together. “Getting along” in a community is a function of evolution and our very being, and so is strife, though the later is more akin to barbarism like hate and tolerance than civility like love and understanding. How do we reach non-zero sum (win/win) Pareto optimal situations that are more akin to mutualism than parasitism in a meta context? Keep reading…

not logical. And if people wish to quantify happiness it can get ugly (see the poaching examples above). This is complicated by opposing groups feeling superior, and more wronged than the other group in reaching a resolution on how to cut the trail cake. On that note, the correct focus is meta: are trail user division rules good or bad for trail x, and why? The incorrect focus is: which trail use type is ‘moral’? Related to the focus problem is the problem of our very selves, our genes, and how they tell us to think. Evolution equipped us with group cohesion, not meta-morality. That’s why some people slip into focusing on the ‘morality’ of a user group, not how to get along and use a trail together. “Getting along” in a community is a function of evolution and our very being, and so is strife, though the later is more akin to barbarism like hate and tolerance than civility like love and understanding. How do we reach non-zero sum (win/win) Pareto optimal situations that are more akin to mutualism than parasitism in a meta context? Keep reading…

Rivalry

In the late 80’s ski resorts, or perhaps skiers more-so, were up in arms about snowboarding. Many arguments were made as to why snowboards should/not be on the mountain. It was an all-out skier vs snowboarder war in some circles. Twenty years later, I’m not aware of any resort where there are snowboard only, or ski only runs, but they may  exist, they typically are on private property. I imagine the same rivalries I remember as a child still exist somewhere: skater vs bmx, surfer vs body boarder, jocks vs ________, heavy metal types vs. punkers etc. On trails, or life in general for that matter, some people have not grown past this us-versus-them false dichotomy mindset: hiker vs biker, cross country skier vs snow mobiler, mountain biker(mtb) vs hiker vs equestrian, dirt bike vs quad vs jeep, dirt bike vs mtb… and even with-in their own kind: blue-blazer vs through hiker, trail runner vs hiker, trekking pole vs free form, compass vs gps… Mountain biking is rife with rivalries: cross country mtb vs free ride mtb vs all mountain mtb, gears vs no gears, small vs big wheels, suspension vs rigid, lycra vs baggy, and even mtb vs roadie although they don’t even share the same space! All of this is dumb. I understand that, and I don’t tolerate it. Because someone does not do what someone else does on a trail does not mean they are against each other or they are there to ruin each others day, although quite often that mindset is the case when guts are used, not brains. It’s a lack of understanding, a lack of reason. In some instances certain users might clash, but its not as if there is a conflict of interest between an entire group and another group. At least on the surface…

exist, they typically are on private property. I imagine the same rivalries I remember as a child still exist somewhere: skater vs bmx, surfer vs body boarder, jocks vs ________, heavy metal types vs. punkers etc. On trails, or life in general for that matter, some people have not grown past this us-versus-them false dichotomy mindset: hiker vs biker, cross country skier vs snow mobiler, mountain biker(mtb) vs hiker vs equestrian, dirt bike vs quad vs jeep, dirt bike vs mtb… and even with-in their own kind: blue-blazer vs through hiker, trail runner vs hiker, trekking pole vs free form, compass vs gps… Mountain biking is rife with rivalries: cross country mtb vs free ride mtb vs all mountain mtb, gears vs no gears, small vs big wheels, suspension vs rigid, lycra vs baggy, and even mtb vs roadie although they don’t even share the same space! All of this is dumb. I understand that, and I don’t tolerate it. Because someone does not do what someone else does on a trail does not mean they are against each other or they are there to ruin each others day, although quite often that mindset is the case when guts are used, not brains. It’s a lack of understanding, a lack of reason. In some instances certain users might clash, but its not as if there is a conflict of interest between an entire group and another group. At least on the surface…

On the surface, rivalries amount to the “genetic fallacy” (or origins fallacy, or virtue fallacy), where we are grounded in our camp, and suspicious of anyone outside that camp. The ‘outside camp’ might be something new or old, or something foreign. Just how real the outside camp is in terms of a threat is debatable. This is a variation of the ‘argument from history/tradition’ discussed later.

Near and Far-Sighted Theses

Some members of trail user groups can start to slip into a misguided groupthink where they feel the us vs. them “vibe” and really start to believe it and live it. Group  bias messes up the trail user resolution process. Individuals start to forget who they are, or what it means to be “oneself,” and think as if everyone is them. In the process they forget all trail users have their own reason for using a trail, the reasons are many, but quite often the same in spite of our differences from within, and from without our particular group(s). If this is forgotten people fall into what Joshua Greene calls “Tragedy of Commonsense Morality” (see this interview with Greene). When we forget individuals we can fall into group uber allen (over all), and the tragedy is that groups have a hard time cooperating to come to an agreement (from within, and from without). In addition, to complicate things, there are individuals that wish to force their view or self-interest on the group so the group becomes a collective version of them. This second problem amounts to what I’ll call the type-A-hole, or the type-Alpha-hole: in pushing A’s agenda on others (B-Z), A is a hypocrite as A should keep it to themselves as every single B-Z is there own person, not an A to do with as A wishes. A key in group dynamics is to not be a type-A-hole: understand to each their own, and avoid tolerance sprinkled with hate. It comes down to consistency. Type-A-holes are inconsistent in their application of getting what they want. The key is not in Democracy, certainly not type-A-autocracy, but honest-to-goodness consensus and direct/participatory-democracy (see Elinor Ostrom’s solution at the end of this paper). But can individual and collective sovereignty ever occur in concert if they can be at odds- thesis vs anti-thesis? It’s not easy street, but consensus is a means to take into account Locke’s consent theory. The question is, who sits at the table of decision-making trail policy to divide the cake? And when dividing how do we measure what’s fair?

bias messes up the trail user resolution process. Individuals start to forget who they are, or what it means to be “oneself,” and think as if everyone is them. In the process they forget all trail users have their own reason for using a trail, the reasons are many, but quite often the same in spite of our differences from within, and from without our particular group(s). If this is forgotten people fall into what Joshua Greene calls “Tragedy of Commonsense Morality” (see this interview with Greene). When we forget individuals we can fall into group uber allen (over all), and the tragedy is that groups have a hard time cooperating to come to an agreement (from within, and from without). In addition, to complicate things, there are individuals that wish to force their view or self-interest on the group so the group becomes a collective version of them. This second problem amounts to what I’ll call the type-A-hole, or the type-Alpha-hole: in pushing A’s agenda on others (B-Z), A is a hypocrite as A should keep it to themselves as every single B-Z is there own person, not an A to do with as A wishes. A key in group dynamics is to not be a type-A-hole: understand to each their own, and avoid tolerance sprinkled with hate. It comes down to consistency. Type-A-holes are inconsistent in their application of getting what they want. The key is not in Democracy, certainly not type-A-autocracy, but honest-to-goodness consensus and direct/participatory-democracy (see Elinor Ostrom’s solution at the end of this paper). But can individual and collective sovereignty ever occur in concert if they can be at odds- thesis vs anti-thesis? It’s not easy street, but consensus is a means to take into account Locke’s consent theory. The question is, who sits at the table of decision-making trail policy to divide the cake? And when dividing how do we measure what’s fair?

If a trail use situation becomes us vs. them, who should win and why, should there be war at all, and how do we strip away the cause of conflict? To do this we have to maximize happiness for all (A-Z) and strive for non-zero sum. This is incredibly hard to do if people are type-A-holes. As Greene says, “just try to be a little less tribalistic.” To see how to be less ‘tribalistic’ we have to examine what the “best” ideas are for/against shared vs. single or restricted use trails. We can’t do this effectively if beliefs and group bias get in the way.

The Game of Adding Up to Zero

One example of bias in the single vs. shared use debate concerns game theory and the notion that any shared use resolution is zero-sum, or the gain of one group is a loss to another. This often happens with shared use resolutions as one group, or a few individuals in that group, feel they have lost something by sharing. The result people see depends on their perspective. Loss sentiments are especially apparent when a single use trail is converted to a shared use trail. It doesn’t sting nearly as bad when it’s decided from the get-go that a new trail will be shared use. If two groups have to share it could be a non-zero sum if its viewed as both groups getting to use the resource/trail, or a zero-sum where its viewed as one group giving up exclusivity rights. Of course there are three or four other user groups that may lose if the trail is only open to two.

Trail Ecology 101

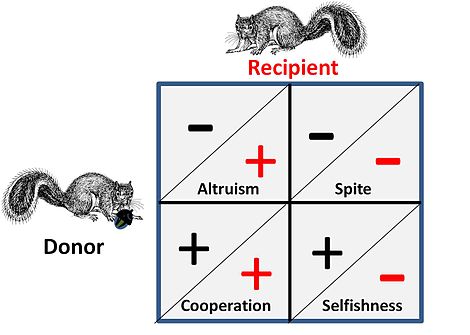

Similar to the ideas of non/zero sum in Game Theory are ideas in Ecology that relate to trail use issues:

- commensalism– one organism benefits and the other does not benefit +/0 (single use)

- mutualism– both organisms benefit +/+ (shared use)

- parasitism– one organism benefits and the other pays +/- (shared use or single use)

- altruism– which can be framed as any of the proceeding three, but usually as a type of parasitism +/- (shared use or single use, where one group claims to have been philanthropic. What’s bad are situations where the philanthropists ‘give’ the dregs to another user group– trails with no views, no flow, or places of interest, or multiple maintenance problems etc.)

The first two relationships are “cooperation.” Altruism may be seen as ‘charity.’ Like many ethical-type premises, how altruism is framed may change how its justified or explained. Which is exactly what tends to happen when figuring out how to divide trails up between users (as noted above).

Joan Roughgarden lays out ‘social selection‘ in her book the Genial Gene. Her argument, similar to Greene’s, is that mutualistic cooperation leads to biological success. She focuses on the success of ‘tribes,’ Greene on how tribes can be at peace and succeed together. It’s interesting to consider the “moral molecule” (oxytocin) as behind some of our interactions, and whether it might explain social selection and group dynamics, which is close to what Greene studied.

Tribal Vision Education

In the end, dealing with loss is simple when there are tribal rivalries, barbaric tendencies, and notions of injustice: “civilize” through dialogue in order to educate. Not everyone will go away with honors on their diploma, or a diploma at all for some. When all sides think they are educated about the other side’s shoes the debate over use can become a “battle” for trails or a war (depending on who you ask). In that sense, education, to paraphrase Sun Tzu, is key because “if you do not know your enemies nor yourself, you will be imperiled in every single battle.” The division of the trail cake doesn’t have to be a war, but quite often it is. The question is how do we find peace, how do we limit war and loss, and maximize happiness? Some people are happy being dumb, so be it, but education and empathy can go a long way towards the reduction of dumbness, finding peace from the start and after the dust has settled from a battle. One way to start was already mentioned, learn to understand, of course that’s often achieved through education where learning curves and results vary…a Caring C average would be nice.

In the end, dealing with loss is simple when there are tribal rivalries, barbaric tendencies, and notions of injustice: “civilize” through dialogue in order to educate. Not everyone will go away with honors on their diploma, or a diploma at all for some. When all sides think they are educated about the other side’s shoes the debate over use can become a “battle” for trails or a war (depending on who you ask). In that sense, education, to paraphrase Sun Tzu, is key because “if you do not know your enemies nor yourself, you will be imperiled in every single battle.” The division of the trail cake doesn’t have to be a war, but quite often it is. The question is how do we find peace, how do we limit war and loss, and maximize happiness? Some people are happy being dumb, so be it, but education and empathy can go a long way towards the reduction of dumbness, finding peace from the start and after the dust has settled from a battle. One way to start was already mentioned, learn to understand, of course that’s often achieved through education where learning curves and results vary…a Caring C average would be nice.

In an effort to boost caring, don’t “tolerate” dumb ideas about why a trail should or should not be shared or single use. “Understand” the legitimate arguments, and some of the tribal/user group rivalries. What follows below are some shared use vs single use arguments adapted from Jim Hasenauer, an ex-IMBA President (from this article). I took what I thought were his best ideas, discarded what I viewed as his weaker points, and added some thoughts of my own.

Before I begin, I have used the term “multi use” many times, and I don’t think its newspeak or a bad term, but I prefer to say “shared use” because to me it conveys understanding.

Why Shared Use Trails?

- A shared use trail accommodates the needs of the most users.

- A shared use trail system disperses users across that system.

- A single use (or restricted use) trail within that system will concentrate users groups on both single and shared use trails in that system.

- Higher concentrations may increase the chances for conflict.

- Sharing trails builds a trail community.

- Sharing trails unites users to cooperate to preserve and protect a common resource.

- Encountering other users on a trail offers the opportunity to meet and establish mutual respect and courtesy (but hopefully not damage it if someone is rude).

- Separate trails breed ill will between user groups.

- Separate trails may increase territoriality and in turn into conflict.

- Separate trails may reinforce or create rivalries or ‘tribalism’

- Shared trails are the most cost effective trails for land managers.

- Single-user trails increase demands for the construction of additional trails to serve other single user groups.

- Shared use trails require less staff as monitoring and enforcement is simplified.

- Shared use trails require fewer signs.

- Sharing trails provides the opportunity for bigger joint-force voluntary trail crews. (or the possibility of a synergistic rivalry or competition in this regard, both good and bad).

- Shared trails enhance or increase peer regulation of the shared resource.

- Shared use trails can encourage responsible experienced users to educate outlaws, novices, and “haters.”

- Separate trails increases ecosystem impacts by adding extra trails to trail systems or concentrating user groups.

- Shared use outcomes are mutualistic(explained below).

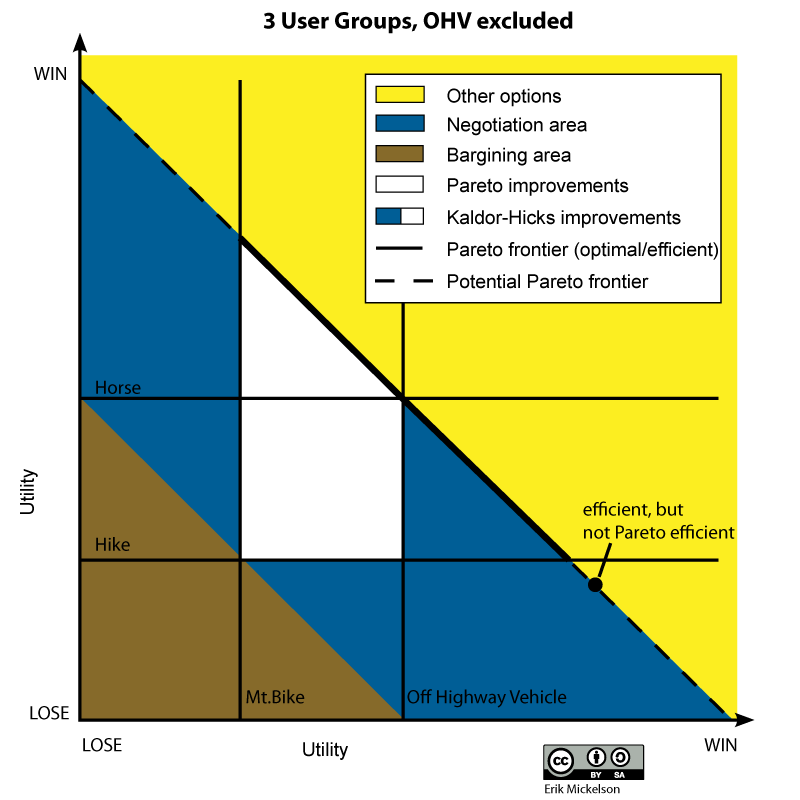

- Shared use trails can be Pareto optimal (explained below), non-zero sum win/win, and sometimes parasitic zero-sum win/lose or lose/win. Single use trails are Pareto inefficient.

Why Single Use Trails?:

- May be needed for crowded small trail systems not capable of spreading users out. However, this argument is weak in that one-way trails and days for certain uses on certain trails can act as a spreading mechanisms.

- May be needed for large trail systems with crowded trail heads. Single use feeders may be needed to bring users into larger shared use network.

- May be needed for race training.

- May be needed for skills and general trail training.

- May be needed for specific trail difficulties like advanced rugged terrain.

- May be needed to provide safety measures (such as horses on a narrow cliff-laden trail or OHV trail).

- May be needed to protect land and/or water, and biota.

- May be needed to provide sanctuary* or user group experiences (see below) away from other user groups.

The “Sanctuary” Argument for Single Use Trails

The argument for an exclusive trail right is hard to justify, especially when using the “argument from sanctuary,” as I call it. It might also be called “user experience.” If the seven other arguments can’t be made above, people may resort to the sanctuary argument. This argument boils down to not wanting to encounter “other” modes of transportation on “their” mode trail. They don’t want to share. Sharing is one of the first things most people learn to do as children interacting with others. It is painful to have to even present the ideas below, but it is only in an attempt to confront poor single use arguments, and to make our world more just and compassionate (in my mind anyway).

The argument for an exclusive trail right is hard to justify, especially when using the “argument from sanctuary,” as I call it. It might also be called “user experience.” If the seven other arguments can’t be made above, people may resort to the sanctuary argument. This argument boils down to not wanting to encounter “other” modes of transportation on “their” mode trail. They don’t want to share. Sharing is one of the first things most people learn to do as children interacting with others. It is painful to have to even present the ideas below, but it is only in an attempt to confront poor single use arguments, and to make our world more just and compassionate (in my mind anyway).

The argument from “sanctuary” is hard to make and in turn discredit, and I don’t know that it has to be discredited, although it has several issues to contend with compared to the other seven single use needs mentioned above. What follows isn’t meant to belittle, or compare, the plight of people of color or various religious sects and their fight for dignity and civil rights, but to some degree a comparison can be drawn to the issue of trail access, and single versus shared use.

The argument from “sanctuary” is hard to make and in turn discredit, and I don’t know that it has to be discredited, although it has several issues to contend with compared to the other seven single use needs mentioned above. What follows isn’t meant to belittle, or compare, the plight of people of color or various religious sects and their fight for dignity and civil rights, but to some degree a comparison can be drawn to the issue of trail access, and single versus shared use.

- Public land is not a country club, i.e. “sanctuary” for unbalanced exclusionary privilege. Exclusivity rights, or rights to discrimination, exist only for fully private clubs on private land.

- The sanctuary of Apartheid ended in 1994, the sanctuary of Jim Crow segregation ended in 1964/5, but in a sense they both continue on in trail regulations as bikers, hikers, and horseback riders (and OHVs) are segregated, and/or excluded from various trails. In trail law Jim Crow survives. However, there is no Plessy v. Ferguson guaranteeing “equal, but separate” sanctuaries for all. There is also no Brown vs. The Board of Trail Law. Currently, trails are places where certain kinds are excluded at the discretion of governmental officials, be they State, county, or city, who forge is out of ought.

- Open access to ALL on ALL trails isn’t likely to ever happen, and I can appreciate the desire for hikers, and/or horseback riders to “experience” a place(i.e. “sanctuary”) where they will only run into their own kind. However, as it now stands, in 2014, mountain bikers have maybe five legally recognized “separate, but equal” facilities on public land. OHVs face a similar ‘plight,’ but are much more well (or worse) off depending on the State. Is this outright racism/bikism? I’m pretty sure horses share the same ‘plight’ and always have to share trails (at a minimum with hikers). I have also seen some mtb specific and OHV trails where it is not recommended hikers or horses enter, but it is not forbidden.

- Would justice would come in measuring the miles of user segregated trails vs. user numbers, and dividing up and segregating trails on a truly “separate, but equal” basis? or providing equal access to all on every single trail that exists? or a combination of single and shared use? The question is how much, and who decides, and how and why?

- Justice comes with Pareto optimal outcomes, and they should be sought (explained below).

- Another argument from sanctuary involves noise and/or poop and loose tread. Bikes can be noisy at times, on the other hand they can be so quiet as to scare people. OHV and horse use can make very loose tread, usually not pleasant for hikers and bikers. Other than not being able to ask the horses themselves, I’ll assume most users do not like to encounter poop on the trail. I can see the argument for wanting a sanctuary to escape some of these unpleasantries. However, other than the loose tread or excessively loud OHVs in small or crowded trail systems, most of these end as fast as they start when users pass the unpleasntry. Striving for absolutely zero unpleasantries seems like a goal to strive for, but at the same time a little absurd all things considered.

- Perhaps the best argument from sanctuary is tied to the argument for “safety” (#6 above). Consider, for example, certain highways where bikes and pedestrians are not allowed for safety reasons. Safety may be a means to justify segregation or exclusivity, but it’s not 100% valid.

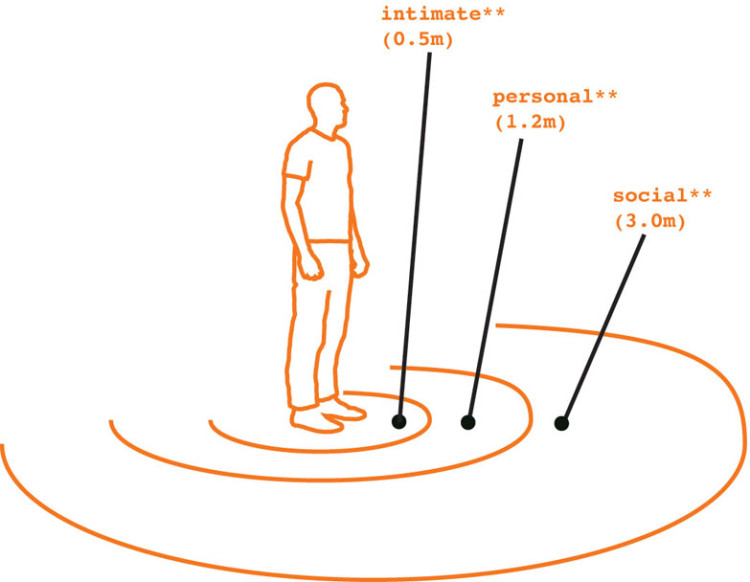

- The main trail safety issue is speed discrepancy. I can think of no other issue, beside collisions with other users, that can justify single use trails better than speed safety.

- If speeds can be reduced for bikes to trail running, and maybe horse galloping (or running?) speeds, is that enough? Dirt bikes and quads can also be slowed to some extent, but its typically not the experience that user group seeks. Of course there are some mountain bikers that desire to obtain speeds near or on par with OHVs.

- Mountain bike speeds can be controlled with grade and turn manipulation (more on the science/physics in a forthcoming trail science page).

- Blind turns and intersections can be addressed multiple ways. The speed and blind turn arguments are design arguments, not arguments for restricted use. Unless a reroute design solution to blind turns and speed problems is restricted for environmental reasons, there is no reason why a single use trail can’t become safe for shared use. Even with reroute design limitations due to environmental constraints, chokes points can be used to slow users down.

- If speeds can be controlled to limit discrepancies, the safety argument from a speed standpoint fails. If the speed/safety argument fails, we are left with the argument from sanctuary.

- One-way trails are another method of reducing speeds, as oncoming traffic approach speeds are much higher on two-way trails than one- way trails.

- I’m guessing that in most cases the ones making a stink about shared use trails have had a bad experience with another user group. One question to ask here is: how likely is it that there will be a bad experience with their own user group on a single use trail? This question is important because most users will never have a trail to just themselves, or risk-free of encounters with their same user group. That said, how is conflict from within different from without, if it is conflict they wish to avoid in not wanting a shared use trail? In other words, to enlist the sanctuary argument does not guarantee sanctuary from your own user group, so what’s the difference if a trail is shared and the sanctuary seeker has no conflict with another user group?

I don’t have answers to some of the harder questions asked above (2.2, and 5), and I don’t know that they can be answered accurately. We can try, but I won’t attempt to do that here.

Seeking Sanctuary in History or Tradition

It’s worth addressing instances where the sanctuary argument may be skirted and morph into arguments of tradition and history. This probably happens because the argument from sanctuary is hard to make or put into words, though there is a sanctuary analogy made several paragraphs below.*

- Arguments from “tradition” do not justify a single use trail, and do not tie to ‘sanctuary.’ To elicit tradition is to call up the ghosts of the past, and is also an “ought” (described earlier). If it is argued that a trail is to be single use because of tradition, then so too can it be argued that at one time there were no trail rules, so too can it be argued that segregation and prejudice were tradition at one time…why should segregation and prejudice on trails continue? I’ll grant that at one time we ONLY walked/ran on trails, but at the same time at one time we had no shoes either.

- Arguments from “history”are very similar to the “tradition” argument, and do not justify a single use trail, and do not tie to ‘sanctuary’ either. Historical arguments may be tied to tradition (a fail as seen above), or used alone. If used alone, it may be argued that historically (or traditionally) this trail had only one use, or only two uses, we can’t allow a second or third… What then do we do with trails where a use does truly become ‘incompatible’ and is banned? Can we change in only one direction and not the other, why? Historically, there was a time when certain public facilities and businesses were for one group and not another. Thankfully, logical reasoning and the law sorted these ethical issues out. Lastly, adding or deleting a use will never take away the history of the past, it will only add to that history. Arguing a change in the present “ought to not happen” because its better or worse for the past or future has no clear answer so it can’t be used as an argument for trail use type(s).

Begging on a Gamble in a Black and White Bandwagon on a Slippery Slope called Anecdotal

Besides the logic fallacies discussed elsewhere in this document, the trail use debate usually carries the following logic problems or fallacies.

The Gambler’s Fallacy (Monte Carlo fallacy, or maturity of chances) may be encountered. Example: After many weeks/months of not having a negative trail experience with another user, including trail poaching, a user may feel they are due or overdue to witness it again. We tend to make or seek patterns where they may not exist, like after twenty positive encounters expecting one negative experience because twenty encounters ago there was a negative one.

Gambling often amounts to the informal fallacy of “begging the question.” The dice are loaded with assumptions (like fear and distrust of another user type), and rolls that affirm assumptions prove nothing except an assumption, not necessarily reality or truth. For example, “opening up trail x to another use will invite users to poach nearby single use trail z because trail x intersects trail z.” It is a risk, but begs the question as to how frequent poaching will occur, if at all.

The trail use debate is usually presented in very black and white terms. The black and white fallacy is know by several other names that help describe the logic issue by this fallacy: false dilemma, the either-or fallacy, false dichotomy, fallacy of exhaustive hypotheses, the fallacy of false choice, the fallacy of the false alternative, or the fallacy of the excluded middle. A crude response to an excluded middle or false dichotomy is that “there are more ways than one to skin a cat.” However, with trails, the solution is usually very black and white: these trails for these uses, and these for these, this is how the cat will be skinned– the end. Rarely are alternates considered, like one way trails, single use trails for other user groups rather than just hikers, and various uses for various days. The false dilemma of “opening up a can of worms” to conflict is quite often used as a single use proponent talking point, as described above in the question begging example of trails x and z.

Black and white gambling and begging are usually combined with the “slippery slope” fallacy where if trail x opens then eventually trail z will be poached, or eventually trail z may become shared use…shared use trails will “spread like cancer, killing single use trails.” Slippery slope arguments are typically an “appeal to emotion.” The denial for a shared use trail based on protecting single use trails is a slippery slope argument based on fear and hypothetical situations. Without actually striving for a well thought out trails plan and solutions to real inequality etc. the shared use debate is not advanced, just agitated along with the emotions and prejudices of users.

One way to cut the trail cake is by “popularity” or user group numbers in the area to be split. Another is open trails to all. Lets assume the former and expand the local borders out to the entire state or nation and conclude something like the following: “being that there are 400,000 people that say they hike, 20,000 that mountain bike, 10,000 that ride horses, and 50,000 that ride ATVs/dirt bikes, the trail cake miles will reflect this reality: 400:20:10:50.” This “solution” to the division of the trail cake is logical, but this is a form of the “bandwagon” fallacy or an “appeal to popularity.” Should popularity alone justify a mile-per-mile split? What if we consider things like the distance a motorcycle or bike can travel versus a person walking, not to mention how some uses are compatible, and not necessarily antagonistic.

Whether a single use proponent has actually had a bad encounter or fears them based on testimonials, what these people might not consider is that the encounter was just “dumb luck” and they should refrain from jumping into the “gambler’s fallacy.” Further, one or more bad encounters could amount to the “anecdotal fallacy,” and by no means reflect evidence and/or data to support the “fact” that their isolated experience will translate to others with frequency (however frequency may be defined). Concluding that an anecdotal experience will always occur in a pattern with frequency is poor logic. This isn’t to say that someone does not have a right to finding a sanctuary should they wish to seek it.

Come Join Us or Get Lost

To ask someone who only hikes to start riding a bike or horse, or someone that rides/runs/hikes to only “be” one and not three is very similar to asking a certain race or religious creed to convert to another. Those users do what they do because it is who they are. Is it fair to ask them to change in this regard? It’s like asking an is to become another is because they ought to. It’s like asking someone to kill themselves. Why should there be trail discrimination against the very nature of who people are? More simply, why should there be discrimination, and rights privileges? These are hard to answer, and should be considered deeply, not in a cursory manor, when deciding how to restrict trail use.

To ask someone who only hikes to start riding a bike or horse, or someone that rides/runs/hikes to only “be” one and not three is very similar to asking a certain race or religious creed to convert to another. Those users do what they do because it is who they are. Is it fair to ask them to change in this regard? It’s like asking an is to become another is because they ought to. It’s like asking someone to kill themselves. Why should there be trail discrimination against the very nature of who people are? More simply, why should there be discrimination, and rights privileges? These are hard to answer, and should be considered deeply, not in a cursory manor, when deciding how to restrict trail use.

*It could be argued that when you enter the church/sanctuary of hiking use, you practice hiking, when you enter the church/sanctuary of hiking and horse back riding you don’t practice mountain biking. I can appreciate this, and think this is the single use position. It can also be the shared use position, but the shared use position may be closer to a “mobile sanctuary view” that sees the trail as the path where every user carries their own church/sanctuary and practice with them. Different user types pass by each other on the same path with different world views, acknowledging (or not) for a moment the others practice using the same trail means to get what they want, though in a different mode.

With the mobile sanctuary view some of the users understand they can’t/shouldn’t change who they are and act in-kind to others: meta-morality. The single use position is less meta and more tribalistic in its approach. Single or shared use, some users tolerate differences with a little hate inside, still others look for war and understand little to nothing (even in their own tribe). Why can’t we all “just get along”? (Greene explained why as noted earlier). Both approaches beg the question as to who decides which type of trail use church should be built or open, how many/to whom, and who should pay how much, and why?

With the mobile sanctuary view some of the users understand they can’t/shouldn’t change who they are and act in-kind to others: meta-morality. The single use position is less meta and more tribalistic in its approach. Single or shared use, some users tolerate differences with a little hate inside, still others look for war and understand little to nothing (even in their own tribe). Why can’t we all “just get along”? (Greene explained why as noted earlier). Both approaches beg the question as to who decides which type of trail use church should be built or open, how many/to whom, and who should pay how much, and why?

Seeking Sanctuary in The Appeal to Nature Fallacy

One of the common misapplications of reason in the trail use debate involves the appeal to nature fallacy. The fallacy follows an is-ought line of reasoning: x is natural, x ought to be right, and similarly, y is unnatural so y ought to be bad. The argument assumes because something is natural it is good. This is what mountain bikers, OHVs, and sometimes equestrians face, or even hikers if you consider trekking poles unnatural. If we follow the premise to its purest logical end there would be no trails at all in Wilderness because trails are not natural…at least trails constructed with tools. The only “natural” trail would be a trail beaten in by walking it barefoot, and naked. In this sense, where do we draw the line on what’s natural, and do we have to? Wilderness trail rules draw the line using the appeal to nature fallacy. To be fair, just and consistent, trails would not exist in Wilderness at all, even if they were only built with hand tools not machines. Even hand tools are not natural. Blazes would not exist either, neither would signs within the boundaries, and users would enter naked and shoeless. Yes, this is a somewhat silly rebuttal, but so is the appeal to nature argument. What’s more silly is that in reality people can go wherever they want in Wilderness, trail or not. While I agree with this freedom to roam, how this correlates with keeping it wild by allowing our presence at all undermines the idea behind Wilderness to begin with. This is why the appeal to nature fallacy fails in this case. Wilderness designates a wild place, except for the oughts it bases on the natural fallacy. Why allow people to go wherever they want, but at the same time ban bikes from actual trails in Wilderness? Bushwhacking all over creation does more harm than allowing bikes to stick to a trail. Why not keep unnatural bikes and unnatural hikes on the unnatural trails? What’s even more peculiar is that bikes are less likely to spook birds than other modes of transportation. Ironically, the thing most likely to scare birds are birders making predatory moves stalking birds with binoculars taking minutes or hours to pass a nesting area or hang-out, not seconds as is the case of bikes.

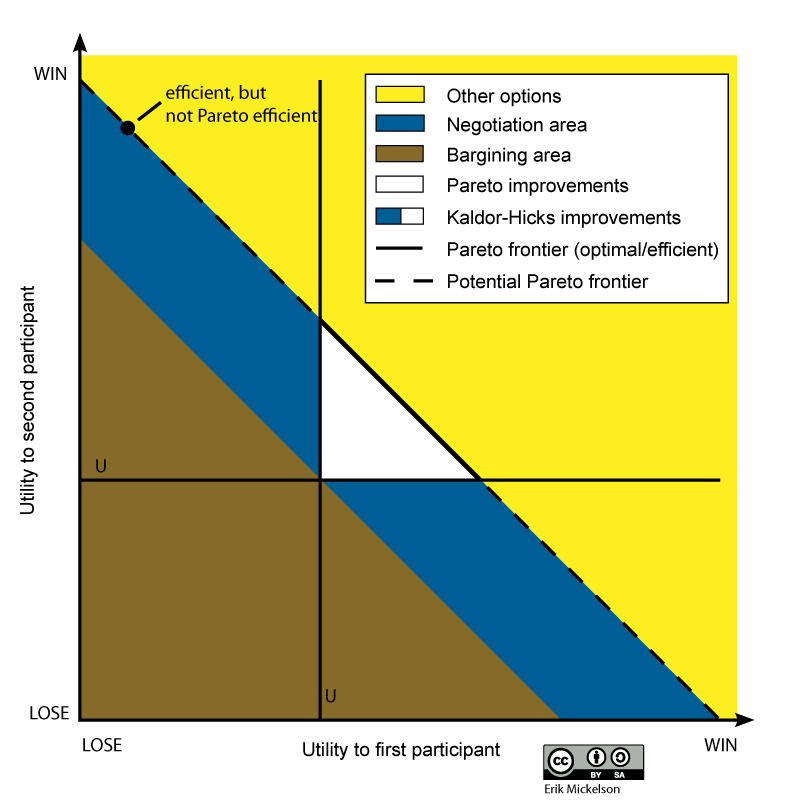

Two Trails: Pareto, and Kaldor-Hicks

Pareto “efficiency” (or optimality) occurs when there is a win-win for all. Inefficiency occurs when the allocation of a trail to one person/user group results in another person/user group being worse off. Optimality or “efficiency” occurs when there can be no more Pareto “improvements” (the inefficiencies are gone).

A Pareto “improvement” occurs when one person/user group improves their situation without making another person/user group worse off.

Shared use trails are Pareto Optimal/Efficient as no further improvements can be made as everyone is in a ‘preferred position’ (the “ought” is now just an “is”).

It can be debated that sharing can leave some users worse off, but this depends on who you ask. Some users will not care that they have to share, and some users may practice multiple religions. Pareto efficiency points to the allocation of resources, and perhaps equality, not necessarily desirable distributions. Nevertheless, Pareto inefficiency is to be avoided, efficiency should be sought, especially with public resources. If there is inefficiency, as in the case of restricted use trails, there is always room for Pareto improvement by sharing, although there may be detractors crying foul about their decline in well being. Kaldor–Hicks efficiency occurs when Pareto improvements are made, but some person/user group says they are less well off, and because of this they are compensated (real or apparent) for their apparent (or real) loss so there is a real Pareto improvement. However, even Kaldor–Hicks efficiency can decrease well being, while Pareto efficiency results in every party being better off (or at a minimum no worse off). Quite often Kaldor-Hicks is the reality of trail divisions, if there is “compensation.” Pareto improvements are Kaldor–Hicks improvements, but Kaldor–Hicks improvements are not always Pareto improvements.

Kaldor–Hicks efficiency occurs when Pareto improvements are made, but some person/user group says they are less well off, and because of this they are compensated (real or apparent) for their apparent (or real) loss so there is a real Pareto improvement. However, even Kaldor–Hicks efficiency can decrease well being, while Pareto efficiency results in every party being better off (or at a minimum no worse off). Quite often Kaldor-Hicks is the reality of trail divisions, if there is “compensation.” Pareto improvements are Kaldor–Hicks improvements, but Kaldor–Hicks improvements are not always Pareto improvements.

A shared use trail “X” with two uses could become a trail with three uses. Another trail “Y” could go from two uses to one. If the loser in “Y” is the winner on “X” (or another trail to compensate for loss) it’s a Kaldor–Hicks improvement.

For any trail that is not open to all the situation is Pareto Inefficient, and the fewer the uses the more inefficient the trail, single use being the least efficient. Kaldor–Hicks improvement can offset the inefficiencies with compensation to losing user groups elsewhere, but measuring the offset via compensation is difficult as the location is different. One novel way to “solve” the problem is to have separate use trails very near to each other in the same trail corridor, practically parallel, but the environmental costs are greater. Frequent turnouts and passing areas make more sense.

One Way to Divide The Cake

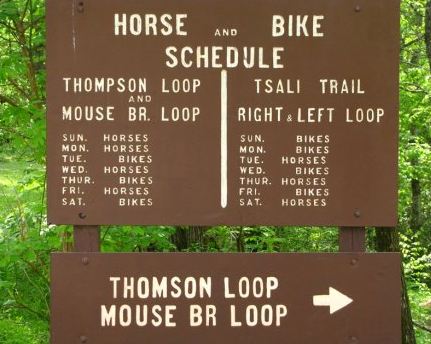

One possible solution if it really needs to come to this (Tsali, NC, also one-way trails if I remember correctly):

The Extra Mile

A trail or trail system can be broken up many ways to share the spoils, or not.

20 miles- who gets what?

- 20 for one user group?

- 20 for all user groups?

- 10 each for two user groups?

- 6.7 each for three, or 13.3 for two and 6.7 for the third… ?

- What often happens is that hikers get 20 miles, and the other user groups have to fight for whatever they can get. There are rarely moments, in this day and age, that another user group gets exclusivity rights for x miles or the privilege to use all 20 while the hikers have to fight for a share of whatever they can get.

- Bikers may argue that they can go two to three times the distance of a hiker, so they should get two to three times more mileage.

- Hikers and equestrians may argue that bikers are a nuisance.

- Bikers might argue that hikers and horses get in the way.

- Hikers and bikers may argue that horses destroy trails and leave unwelcomed surprises on the trail.

20 miles for all is the easiest, perhaps safest, and fairest solution to dividing the cake- everyone gets access to the same cake in its entirety. Just what is “fair” and whether and how to divide or share the 20 often becomes a controversy.

We could approach trails like certain parkways in the Northeast where trucks are not allowed, or approach them like most highways where multiple modes of transportation share the road, or a hybrid of both. If we start with 20 for all and it turns out that problems between users develop, perhaps its time to divide the cake or schedule when certain users have access. The problem with division here is that taking trails away is likely to breed ill will and poaching. Trail use schedules may be a solution. Similarly, if we start with a divided cake and open it to other users, or exclude some users from some sections the results will be the same- ill will and poaching. The best solution is to involve all the stake holders, and confront problems if they arise.

What is fair can be determined, but whether any one person or group sees it as such is debatable, if that is the case is fairness practicable or possible, is inequality acceptable? No answers here, but a fair human will find fairness if they: think and act Golden Rule, wear someone’s shoes other than their own, deal with the users that have stinky shoes, and try to view the impractical through another person’s lens.

Degrees of Comfort

With shared use trails we could say “sharing is caring,” and it makes good resource management sense. Further, some people want to enjoy some trail features and views from a seat AND their feet. Sharing is consistency that leads us away from tribalism towards a meta-moral approach. Single use trails also have their place, but like any use designation, they should be examined carefully and considered on a case-by-case basis. How much inefficiency (Pareto) is acceptable? We all need a “sanctuary,” but I personally struggle with why I wouldn’t want to share because someone is wearing or using the “wrong” gear. It’s hard to put into words without sounding prejudice. Is this because it actually is bigotry? In sanctuary there is comfort, and sometimes it is measured in degrees that can only be felt not explained. But is this the gut or the brain? If it can’t be explained well enough is there a case for division, and who eats the cake?

End

also see: DOT-FHWA Study- Conflicts on Multiple-Use Trails ( more studies )

Dividing the Cake

The work of the Nobel Laureate political economist Elinor Ostrom is worth taking into consideration for trail use divisions as her work focused on managing common resources:

The work of the Nobel Laureate political economist Elinor Ostrom is worth taking into consideration for trail use divisions as her work focused on managing common resources:

“By referring to natural settings as “tragedies of the commons,” “collective-action problems,” “prisoner’s dilemmas,” “open-access resources,” or even “commonproperty resources,” the observer frequently wishes to invoke an image of helpless individuals caught in an inexorable process of destroying their own resources.” (Governing the Commons p.8)

“The “only way” to solve a commons dilemma is by doing X. Underlying such a claim is the belief that X is necessary and sufficient to solve the commons dilemma. But the content of X could hardly be more variable. One set of advocates presumes that a central authority must assume continuing responsibility to make unitary decisions for a particular resource. The other presumes that a central authority should parcel out ownership rights to the resource and then allow individuals to pursue their own self-interests within a set of well-defined property” rights. Both centralization advocates and privatization advocates accept as a central tenet that institutional change must come from outside and be imposed on the individuals affected. Despite sharing a faith in the necessity and efficacy of “the state” to change institutions so as to increase efficiency, the institutional changes they recommend could hardly be further apart.

If one recommendation is correct, the other cannot be. Contradictory positions cannot both be right. I do not argue for either of these positions. Rather, I argue that both are too sweeping in their claims. Instead of there being a single solution to a single problem, I argue that many solutions exist to cope with many different problems. Instead of presuming that optimal institutional solutions can be designed easily and imposed at low cost by external authorities, I argue that “getting the institutions right” is a difficult, time-consuming, conflict-invoking process. It is a process that requires reliable information about time and place variables as well as a broad repertoire of culturally acceptable rules. New institutional arrangements do not work in the field as they do in abstract models unless the models are well specified and empirically valid and the participants in a field setting understand how to make the new rules work.

If one recommendation is correct, the other cannot be. Contradictory positions cannot both be right. I do not argue for either of these positions. Rather, I argue that both are too sweeping in their claims. Instead of there being a single solution to a single problem, I argue that many solutions exist to cope with many different problems. Instead of presuming that optimal institutional solutions can be designed easily and imposed at low cost by external authorities, I argue that “getting the institutions right” is a difficult, time-consuming, conflict-invoking process. It is a process that requires reliable information about time and place variables as well as a broad repertoire of culturally acceptable rules. New institutional arrangements do not work in the field as they do in abstract models unless the models are well specified and empirically valid and the participants in a field setting understand how to make the new rules work.

Instead of presuming that the individuals sharing a commons are inevitably caught in a trap from which they cannot escape, I argue that the capacity of individuals to extricate themselves from various types of dilemma situations varies from situation to situation. The cases to be discussed in this book illustrate both successful and unsuccessful efforts to escape tragic outcomes. Instead of basing policy on the presumption that the individuals involved are helpless, I wish to learn more from the experience of individuals in field settings. Why have some efforts to solve commons problems failed, while others have succeeded? What can we learn from experience that will help stimulate the development and use of a better theory of collective action -one that will identify the key variables that can enhance or detract from the capabilities of individuals to solve problems?”(Ibid, 14)

“Design principles” of common pool resource management (book, audio interview summary):

- Clearly defined boundaries (effective exclusion of external un-entitled parties)

- Rules regarding the appropriation and provision of common resources that are adapted to local conditions

- Collective-choice arrangements that allow most resource appropriators to participate in the decision-making process

- Effective monitoring by monitors who are part of or accountable to the appropriators

- A scale of graduated sanctions for resource appropriators who violate community rules

- Mechanisms of conflict resolution that are cheap and of easy access

- Self-determination of the community recognized by higher-level authorities

- In the case of larger common-pool resources, organization in the form of multiple layers of nested enterprises, with small local common pool resources at the base level.

Also see: PDF- Coping With the Tragedy of the Commons