Why and When or Where Stairs

If it is possible to avoid adding stairs to a trail, strive for that. If you can’t, you didn’t try hard enough, or perhaps there really is no other choice. Many situations could call for stairs, but are they uncalled for? They may be needed as a means to install vital grade reversals on trails that are a little steep, or as a means to push people up in short or long bursts, faster, to reach a certain elevation, or they might be added between a change in direction to make cutting directional changes less likely (i.e. stairs instead of switch backs, perhaps a “step back” or “switch stairs”, more on this below). Some landscapes and property lines, not to mention the impatience of users,* may not allow the luxury of longer trails to reach the same change in elevation that stairs can provide. There are more examples of where steps could be necessary, but I’ll leave it there for now. In my opinion stairs belong in buildings, and of course trails that are too steep for their own good.

*The impatience of users to get up or down the mountain is a hard one to guesstimate, and can make or break the success of steps or a trail with little to no steps. Some questions might help decide if steps are right on your trails: how fit are the intended users on average, what is the history of the trail or area, are most of the trails in the area steep, is it a reroute, repair, or new trail, how far is the destination or intersection, how front or back country deep is the trail, how easy is it to cut switchbacks or walk off trail to go around gargoyles, how rocky is the landscape- will rock steps fit, can local rocks be used, are wooden steps a better option?

We Hate Stairs

Hate is a strong strong word, or maybe strong dislike of stairs, as could probably be gathered from the introduction paragraphs to this page I personally do not like steps, to the point of hating them. Those questions aside, there has NEVER been a time when I have not heard complaints from hikers while building stairs or overhearing hiker conversation where they lament or hate steps. I have been thanked for sure for putting in steps, but it feels like the majority of people would rather not see steps on trails or perhaps use them at all. Maybe some of the thank yous were only people being polite.

We have to go to great lengths sometimes just to stop people form walking around steps, the proof is undeniable that most people would rather not use stairs, SO WHY DO WE KEEP PUTTING THEM ON TRAILS!? In the end I personally hate steps in nature or at least things that look like steps rather than a scramble or what looks like a scree slope or natural rock jumble of lucky random landings and hand holds where users can traverse to the next section of benching. Other people may have other other objections and reasons for avoiding steps, but I assume the main driver is oxygen demand. A rise/run of 7″/11″ (63.6%) or 8″/16″ (50%) grade is a far cry from a sustainable grade of sub 15%. Even a sustained 10% is a lot to ask for many people. On the objective side of things, if the trail is over 15% for sustained distances steps or check step water bars might be useful, on the subjective side how the rise, run and character of step installation are employed can make a difference in how trail users engage and feel about stairs. Water bars and check steps could be a place where, depending on grades, a set of stairs cold be added with some excavation. The diagram below this photo (which was a trail open to bikes btw) might be helpful in thinking about how to add stairs on a steep segment with an existing water bar or check step or an area where that might be planned. Hopefully a grade reversal can be installed instead.

Step Dimensions

My subjective perspective starts with a question of how to get away from the house or building look, mainly the monotony of these standards:

- Typical Building code standards in the US usually fall within these ranges:

- Rise: 4-7.5 inches, usually ~7, usually not more than 7.75

- Rise uniformity: usually very if not exactly uniform (ADA), or not much more than 3/8″ variation!

- Run: 10-12 inches (11 in. minimum ADA)

- Rise+Run usually 17-18 inches (longer runs for shorter rises)

- Landings: typically not less than 3 ft long

- Width: 34-36 inches, usually 36, 44 for emergency exit steps

The problem of moving away from these standards are twofold 1) is that these standards developed based on ergonomic studies of the human body, and 7 fits most people, and most people are the most comfortable and trip less at around 7 inches (I assume however this does not apply to shorter than average people, children, or people that are less physically fit); 2) most people are used to this standard as that is all we know, all we expect, and all our bodies have become accustomed to. Those are two very big hurdles to overcome, and is it worth it or practical and smart to fight them, or stray from a 7 inch rise?

Inclusive Steps

Have you ever walked up or down steps skipping 1-3 7 inch steps at a time? How many consecutive step skips at a time? Why is that? If we believe the 7 inch rise standard, there is no reason to think we could not build 3-4 inch rises with shorter 11-13 inch runs that would be great for all people. The tall and/or fit humans would just skip a bunch of steps if they wanted, the small steps would be there for shorter folks and those less fit, or just tired. Should 3.5 inches be the new standard?

Stepping Away From Ergonomic Standards

Admittedly a lack of uniformity, especially in rises, can be a tripping hazard. And in fact sometimes this is employed to trip up potential intruders and alert the inhabitants that a stranger is in the building unaware of the break in uniformity. Regardless, how do we step away from uniformity in rises and keep them safe(r)? The simple answer is keep rises close, but vary runs and widths. I assume the research is out there on riser differences, but I’ll go out on a limb and say that if the standards or tone is set early, say the bottom or top of a flight that rises will change, then people will not be lulled into a 7-8 inch rhythm. My assumption is that switching from a straight 7, 7, 7… rhythm to 7, 7, 7, 9, 7… etc. is gong to trip people up, but if they know from the outset to be cognizant of variability or the changes are made so visible that it is obvious then tripping will be less likely. Another question I have beyond the mechanics of the 7 inch-ish rhythm, is have we been conditioned to non-variability because that is the standard, or the expectation is that is that steps are a rigid time signature due to the standards we are so familiar with? I don’t know the answer, but I’m intrigued. A simple work around is to have uniform flight sets, say all 8 rises, then change to an all 10 etc.. However, I’m not sure this provides the unorthodox rugged back country rule breaking I’d personally prefer. Getting away with variability in the front country is harder, especially when the paradigm has been set and ingrained.

Step Labor

In short, steps will probably cost more than trail alone, possibly significantly more than the same amount of trail that gains the same elevation. Stairs can be a construction time suck, and for most people walking they are sucky to go up or down being that they demand a lot from our bodies to go up or down. The time suck is in actuality a money suck for those paying for them, and perhaps not to be controversial but a potential profit motive for the builders as time and special craftsmanship is money.

Despite the suck, when done well steps can sometimes be pleasant look at if they “fit,” but I still beg to differ if they are ever pleasant to walk up or down. Depending on how close the stone or timber is to the build location, and how fast the installers are, it is usually more efficient (and perhaps more pleasant for users) to cut new trail rather than install stairs. To elaborate on the time suck, imagine 3 steps at 7 inches high (actually 4 if you count the base step, and who knows how many step edge gargoyles 2-3 or 6-8?). Three steps at a 7 inch rise each is a total 21 inch rise. Depending on the landings or runs, lets assume 12 inches deep each in this case, so it’s 3 feet of trail length. It could be as little as 4 hours to set and crush the steps and gargoyles into place if a skilled person could be so lucky as to have the resources close by on a narrow trail, otherwise it could be 1-2 full days of labor. Again, I can’t speak to all wooden step options, but I assume it is a tad faster than stone steps. Regardless, the same 21 inch rise requires about 22 feet of trail at a comfortable 8% grade (21 inch rise = 1.75 ft/0.08 = 21.875 feet run, but the trail is the hypotenuse so it is 21.94 ft, not much different than the run because the angle and distance is small in this instance). That 22 feet of trail could, in most instances, be cut faster than installing those three steps and a base, maybe 1 hour with an excavator, maybe half a day by hand if duff and rock removal is needed, not a full day. Further, cleaning a grade reversal or deberming a trail is easier than resetting a loose step or gargoyle…or replacing the hair you pulled out because people walked around your art project all for naught. It’s not that labor and repair costs should be the deciding factor of trail vs. steps, but certainly worth stepping back and thinking about before going a route that most people seem to not want anyway.

Beyond The Labor

Worker injuries are also more likely with step construction as rocks might need rigging, and handling heavy objects and dealing with silica dust and high impact repetitive motions are real concerns. Overall I assume the carbon footprint in calories/inch rise is much higher for steps than a trail alone, especially if splitting rocks. I can’t speak to wooden steps here, but would think it changes depending on the design of those steps. Repairs might be slightly easier depending on the circumstances. Beyond that, steps on trails feel and look less natural than a trail with no stairs (to my eyes anyway), but it’s not like switchbacks are ideal either, especially if walls are needed.

There is also a gatekeeping aspect to steps as it takes a particular set of tools and know how to build (and repair) steps versus cut a benched trail and clean out some drains. Those things make steps an ethical dilemma of sorts. Save people money and reduce profits, or not.

One benefit steps can bring is to serve as a means to keep an unsustainable trail layout open with hardening rather than rerouting it to untouched habitat. Steps could be a temporary or long term solution if no reroutes will likely occur.

Sunk Costs And The Future For Bikes, Adaptive Bikes, Skiers, and Horses

One other problem I have with steps is that I want to see more trails open to bikes and adaptive wheelchairs, and cross country skiing in northern latitudes. Not that steps will stop bikes, but it does raise a number of issues and the likelihood of trail conversions from hiking only to multi-use because people might fall for the sunk cost fallacy– that resources and time went into this or that staircase so we can’t open this trail or reroute past all that work. Sometimes it’s time to just walk away and start over, step forward and rise above the past to land on new ground for more people, inclusion. That said, one way to dissuade bikes, at least from going up hiking only trails is to add steps, not the best solution, but it can help. Nevertheless, riding down steps is easy and sometimes more fun than trails without built in hucks or technical trail features. Modern suspension makes step rises almost trivial, and e-bikes could certainly climb some steps without a problem. Short 3-5 step flights can be easily scaled by pedal bikes if riders have the skills and run to do it. Consider these issues if a hiking only trail is near mountain biking trails. There’s one argument for changing those rises and sometimes making cumbersome scramble type rises that step away from the standards. Of course the best bet is to make the trails bikes are on so engaging (and long enough) that the hiking only trails are not worth the effort for most.

Stepping Away From The Paradigm

I can think of no better example of a paradigm than steps on trails, or at least the apparent archetype that I would like to escape, where everything is x inches high, y inches deep, and z inches wide, rigid repetitious standards rather than organic haphazard nature shapes, or rhythms really. One problem with stepping away from uniformity is camouflaging the steps so that it’s hard to tell where the trail is, or where it starts again if it happens to be out of sight. This isn’t to say that a uniform staircase, or uniformity in general is not nice to look at. I also admire a nearly laser cut staircase sometimes, but thankfully nature rarely lets builders get away with that all the time.

Ramps and sloped paving with a few landings is a perfectly feasible alternative to the paradigm. Paving is still labor intensive, but less than steps (or so I think). So is no steps at all, imagine that. The rise issue is perhaps the biggest hurdle, or steps are themselves hurdles for many both physically and mentally.

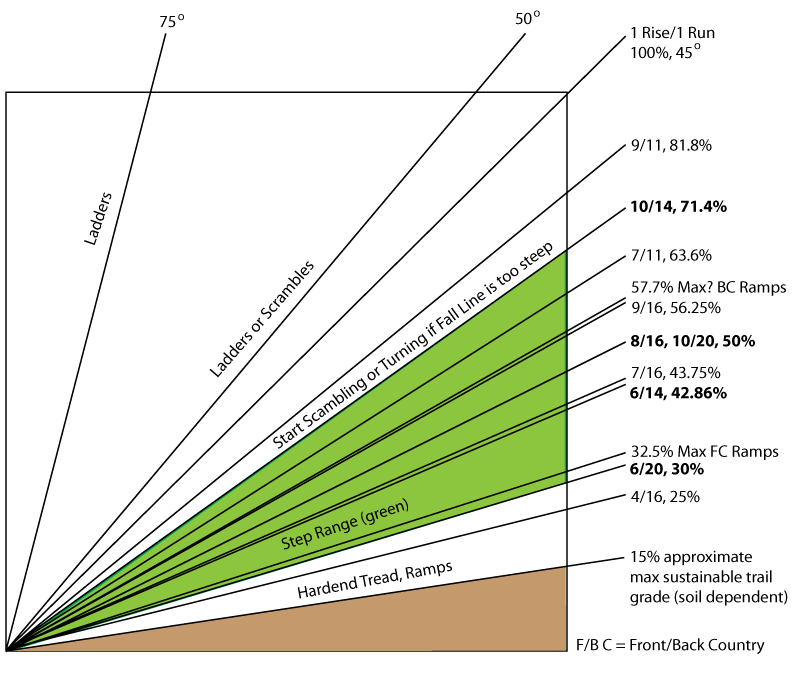

I created the image below as a means to visualize different rise ratios in relation to each other and where ramps or paving might work. Ramps or inclined paving can be problematic if snow and wet conditions are persistent, but is mainly dependent on the characteristic of the rock in question when wet. Some rocks are still textured enough to provide friction when wet.

Rises are usually easy to adjust and usually not a thing compromised in the field. Runs on the other hand are somewhat subjective or at least more likely to be compromised depending on the situation. It is also one way to add variability without changing rises much. Note the large area of green that could be occupied by ramps instead of or in addition to steps. Ramp steps or a combination of ramps and steps could be used side by side or in succession, talk about unorthodox…someone break the damn paradigm.

For some context of the image above, the image below shows some solutions for grades not in the magic 7/11 64% or 8/16 50% range (or whatever the local stones might elicit) if that is what you are going for. Ultimately some excavation needs to be done to make steps work on grades that stray from the 6-9 inch rise of common steps. The formula in the bottom left could be helpful for planning purposes as shooting a 20 foot stretch at 27% with a clinometer can return an approximate number of steps, and with some more arithmetic (not shown) the amount of flights or landings assuming you know the step run lengths can be determined.

I made the “shoehorning” steps image above as a contractor I was working for was struggling with a state employee who insisted that steps should NEVER be put on the fall line (not even 5 or 6), but should ALWAYS be on side hills or bench cut construction. I don’t know where to begin here with the problems that can arise with this rigidity, or the extra expense that putting steps on bench construction elicits, mainly in the addition of walls, but the contractor and I could not talk any sense into the state employee six ways to Sunday. He was right and we were wrong in his mind’s eye. He was a stubborn sob, and ultimately very wrong, as most stubborn people are. I presume part of this had to do with his experience with trail solutions (not necessarily new design) because the only solutions or stairs he had seen (that I am aware of) were on projects where steps had to be added because he or someone else laid trails out at grades over 15% with insufficient drainage, and when “fixes” to poor trail alignments were done the solutions had to be done in situ, and no reroutes were permitted, thus the solution was cribbed/walled stair cases on poorly laid out bench construction. His world was limited in scope, and he wore blinders. He also cost tax payers a lot more money not only from the original poor layout, but also in the extra labor of needing stairs at all, and especially because cribbed/walled stairs are a larger or additional expense beyond steps alone.

Excavation vs Walls

The main point of the image above is that excavation, walls, or large gargoyles are needed when installing stairs on/in trails. The closer the slope is to the magic 7-8/12-16 rise/run the better for the morale of the crew and the timeliness of it all. So do what you can to approach that grade most of the time, all of the time is a stretch. And stand your ground with suborn clients.

Fall Line Steps and Breaking The Sustainable Paradigm

In regards to the NEVER putting steps on or in the fall line the state employee is wrong, some conflation is happening. Trails should not go on the fall line, steps however CAN be placed on/in the fall line. We are talking about rock or wood in this case, or stair case, not dirt! The question becomes how many steps on/in the fall line? I don’t have answer and every tread watershed and average rainfall is unique, so this is a case-by-case issue. Regardless, steps can be placed on/in the fall line, the question remains how many. Certainly don’t go top to bottom with 40+ stairs and no landings if you can help it, and consider what the tread watershed might do to scour the staircase right off the mountain. If there are drains and landings the entire way with some breaks to get water away from the staircase I could see following the fall line for a very significant distance being just fine. A “significant distance” is again a case-by-case site and weather scenario.

The thing about the fall line is that there is no steeper option, no one is going to cut the fall line to get up or down faster as the fall line is the fastest way up/down. This is the one beauty of stairs, you can break the sustainable paradigm and follow the fall line! And that I like! I can follow the fall line and break the mold that is the half rule, hell yeah! But I’ll need stairs or paved ramps to do it. However, some people like one state employee I know somewhere can’t comprehend this logic. Really fit hikers that have an agenda to get to the top ASAP have no reason to bypass the case for the fall line, as the case is already on the fall line, case closed.

Switch Cases, Switch Stairs, or Step Backs

The idea is to not have additive water velocity and/or volume. Steps, especially with gargoyles or bumpers on the sides do a great job of blocking fall line water, but that water can start to follow the gargoyles (and the steps). To me, the solution always resides in rolling contour trails, and I think of steps like water bars, a thing of the past, EXCEPT there are issues of hiker patience and areas where steps or scrambles are the (best) solution/s. In my experience the single hardest trail design concept, especially with hiking, is one of “efficiency.” If hikers are braiding a trail for route B that is a shortcut to original route A, it is an efficiency problem. If hikers are bombing straight down the mountain fall line and skipping the trail or large segments, its an efficiency problem. There are a number of factors to consider in regards to efficiency that could be a book in itself, or more than what belongs on a page about steps, but I will say that it is a hard nut to crack or ponder, especially with shared use trails. One possible solution is marrying new and old schools, if we should compare it as such, and this resides in a possibly novel or new solution for hiking trails, “switch cases,” or a place where the steps are most definitely going to be on the fall line, separating the two rolling contour trails above and below the switch stairs or step back. My personal preference would be for a scramble or many scrambles separated with short resting intervals of contour trails. However, this is also a question of the desired outcomes and possible issues with the paradigm shifts alluded to above. Regardless, a switch case is used to separate two rolling contour trails to reduce short cutting. Again this is going to be a case-by-case stair case, and site selection will be important, if not difficult in many instances.

Best practices (my perspective)

- Try not to put steps in first.

- Contrary to this post’s title, try to put steps “in” trails, not “on” them. In other words, try not to let them float above the slope too much- this is especially important if not going up the fall line as when setting steps on a sideslope the outside/downslope gargoyles could require massive stones or a crib wall, so opt for setting them on fall line if you can, or be prepared to dig a whole lot to make them fit in, otherwise it’s wall or big stone time. Walls or crib stairs add to the time/money suck.

- Pay attention to slope grades as to avoid digging too deep of floating above too high. The ideal hill slope will match the average step slope rise/run, aim for that to minimize digging and floating.

- In my opinion, if you must do “set on top” over “set behind” steps save set on top for the top step/s as it is easier to repair set behind stair stones than set on top, but ultimately repairs or resetting is practically like starting over.

- Monitor grades carefully, and consider this when choosing stone rise/over run to match the grade.

- Remeasure the top step rise goal after each 2-3 stairs as to not under or over shoot the goal.

- Add some 5, 6, and 7 inch stairs aiming for about a 10 inch max rise because walking up a flight of more than four to five 8 inch rises can be painful for some- up or down. It also takes away the rigid repetitive nature and building or city look.

- If rises are varied the best place to do it will be at a landing breaks

- Constant 8 inch rises and constant widths look mechanical and more unnatural than variety. Walking on them is also monotonous drudgery.

- Shoot for 12 inch or larger landings/runs, but variety is also nice here, of course all this is dependent on where they are being put and for what user group.

- More points of contact between each step and gargoyle is more better.

- If a landing has to be sloped, slope it left or right or forward, not back, as to avoid puddles and ice.

- Clean the leaves off in winter and spring, because it’s ugly, and sometimes slippery.

Rises Might Be Subjective, What About Flight Heights?

Ask yourself this when planning: If someone fell down a staircase, how many feet would they fall before stopping? Somewhat unknown of course, but assuming they fall down the staircase from the top of the flight how long before they stop on their face? Consider some landings for rest intervals, and possible accidents. Falling down 20 stairs could really hurt someone, maybe kill them. Consider shorter flight runs with landings so landing is less violent should that occur.

Base Steps

I put this at the bottom for a reason, it’s foundational. Base steps are at the bottom of every stair case or should be, without exception imo, even most landings, although crush fill could suffice in a landing assuming the top step of the landing and gargoyles or wall will keep the fill in place, and water can escape the landing.

I may expand this page at a later date because there is more to say about steps, but for now I also have these to offer:

- front-country-to-back-country-steps-14-methods

- trail-step-calculatorv2

- US Forest Service Trail structures drawings

- California State Parks, Trail Steps Chapter 17

- This is sort of worth a view: the stair event

Trail step estimates Excel Document